We recently covered food allergies and the dietary choices that make your hormones the happiest. We’re going to round out our nutritional plan by discussing two important concepts, blood sugar stability, and what it means to choose “high quality” foods. Making dietary choices that stabilize your blood sugar is one of the most important things you can do for your health.

Read More›in Blood Sugar / Diet and Nutrition / Food Allergies / Hormones / Weight Loss

Why is one person tall and skinny and another short and stout? How can someone eat a 2000 calorie meal and not gain a pound, while another struggles to keep weight off eating a mere 1000 calories a day? When we gain weight, why do some of us pack it on right over that unattainable six-pack, and others only seem to gain from the hips down?

We all have unique bodies. And much of their individuality is determined by how our different hormone-producing glands do their thing. Today, we’re going to talk about that, and how you can tailor your diet to help your glands along, allowing you to look and feel better.

Read More›Is your head spinning yet? With all the information flying around about food – high or low carb, high or low fat, pro or anti carcinogenic, pro or anti inflammatory, synthetic or natural, organic, grass-fed, pesticide free, GMO – how do you make sense of it all? No doubt, dietary information can be dizzying.

Finding a good approach to your diet works best by following some general, baseline principles. If we keep these in mind, wading through the weeds of health information to find the truly good stuff becomes much easier.

There are four areas I typically cover when getting a patient on the right dietary track: Food Allergies, Glandular Dominance, Blood Sugar Stability, and Food Quality. We’ll start with food allergies, and cover the rest in upcoming articles.

Read More›You are never alone. Every second of every day, you’re accompanied by billions of other organisms that live within you, flourishing based upon the choices you make.

This is a good thing.

I’m talking primarily about your digestive tract. Specifically the beneficial bacteria, frequently referred to as the normal flora, that exist in the intestines. While other parts of your body are also populated by friendly bugs, the gut is where their impact is most frequently noticed.

We have a symbiotic relationship with the bacteria in our gut, because humans and the bacteria living inside us both benefit from each other.

The bacteria get a nice, warm, moist, and dark place through which food passes on a regular basis. Compared to trying to survive on a countertop or a random doorknob, our guts are a bacterium’s playground.

In return, these bacteria help us by breaking down food for easy absorption, producing vitamins, and protecting us from unwanted invaders. The unwanted invaders are usually other bacteria or parasites that are pathogenic.

Read More›in Diet and Nutrition / Exercise, Training, and Fitness / Herbs / Hormones / Sleep / Stress

Last time we talked about how we get to sleep, and the two hormones we must manage: cortisol and serotonin. In a nutshell, stress raises our cortisol levels, and also lowers our serotonin levels.

Low serotonin and good, restful sleep generally don’t go together. So what can we do? Address the stress! If we can eliminate or control the things that elevate cortisol, the serotonin in our brain will do its job, resulting in peaceful slumber.

The problem is that most people think stress is one dimensional. Wrapping your head around the idea of psychological stress is pretty easy. Our language is full of clues: being “stressed out” or a “stress ball” are terms people use to refer to someone under a lot of mental or emotional strain.

Read More›Why can’t you sleep? Sleepless nights are a common problem and the causes are numerous. Aside from the obvious causes of sleeplessness — a noisy environment, being sick, congested, or otherwise uncomfortable — there are many people out there who have trouble sleeping and can’t nail down what’s disturbing their rest.

I’ll offer a common explanation for why many people have trouble sleeping. It’s not the only explanation by any means, but I see it in patients frequently enough that it warrants special attention.

Part of the problem is what we accept as “normal”. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard people say something like, “Oh yes, I sleep fine. I get up two or three times a night, but it’s no big deal.” Getting up two or three times a night is not normal. It may be common, but it is definitely not normal.

Read More›in Carpal Tunnel / Exercise, Training, and Fitness / Neck Pain / Numbness

Numbness or tingly hands is a relatively common cyclist’s ailment. Most serious cyclists have experienced this phenomenon at least briefly while in the saddle.

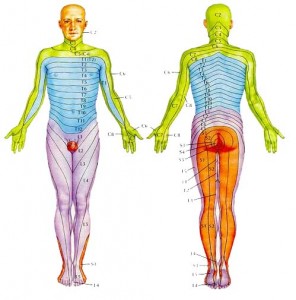

However, its effects can vary widely from person to person. To understand this we must understand some basic neuroanatomy by looking at a “wiring diagram” of the body.

There are many potential causes of tingling or numbness in the hands. These include autoimmune diseases that attack your own nervous system, nutritional deficiencies that impair the ability of your nerves to operate, or structural issues that physically put pressure on the nerve.

An actual impingement – that is, a pinched nerve, even if only while in riding position – is probably the most common reason cyclists experience this phenomenon. Tingling or numbness that only occurs while in the saddle pushes structural issues to the top of our list of possible diagnoses. Since this is what most cyclists tend to experience, we’ll spend most of our time exploring that possibility.

Read More›in Back Pain / Carpal Tunnel / Neck Pain / Numbness / Posture and Ergonomics / Sciatica / Sleep

Last time we talked about sleep, and how many have a skewed idea of what “normal” sleep is.

From waking frequently in the middle of the night, to only sleeping 4-5 hours at a time, to not being able to fall asleep at all, they somehow think that dealing with these issues on a regular basis just makes it part of the ordinary human physiological landscape.

Shoulder, arm, and hand pain, is another group of common complaints patients mention. Any sort of nagging pain in the upper extremity is also frequently accepted as something that is just “part of getting old” or from some previous injury that can’t be helped. Neither is true.

Often, part of the problem is misdiagnosis. Take Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, for example. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, or “carpal tunnel” as it is more commonly referred to, is a condition that affects the hand and is caused by compression of the median nerve, which runs through a passageway in the wrist, a tunnel formed by bones, ligaments, and fascia.

The median nerve sends signals from the thumb, index, and one-half of the middle finger so that you can feel sensations in those digits. It also supplies stimulation to small muscles that control some motions in these same fingers. Sensation and movement on the pinky side of your hand is controlled by the ulnar nerve, which does not pass through the carpal tunnel.

That last point is key. The median nerve runs through the carpal tunnel. The ulnar nerve does not. This means if you experience pain, tingling, or numbness in your entire hand, the problem can’t be originating solely in the carpal tunnel!

It is much more likely that the problem is coming from an area that is affecting both of these nerves simultaneously. Yet we frequently see patients in the office with pain or numbness in their entire hand who have been diagnosed with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

Even worse, surgery is often recommended and performed on these patients, inevitably and unfortunately resulting in no relief from their symptoms. Simply understanding how the nerves are anatomically positioned — the “wiring diagram” of the body, avoids many problems with misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Understanding these relationships is important for complaints besides hand pain. Nerves that supply our extremities originate from the spinal cord in large bundles. As they travel farther away from the cord they branch into smaller and smaller segments, splitting up to cover areas of skin, muscle, and other tissue. The closer to the cord a nerve gets caught, compressed, or otherwise irritated, the larger the area of potentially affected tissue.

Many people are familiar with the radiating pain down the leg commonly called “sciatica.” This pattern of radiating pain from the spine down an extremity doesn’t just occur in the legs. I frequently see patients with symptoms in their shoulder, arm, or hand that originate in the neck. The culprit is the same as in the lower extremity: something around the spine impinges the nerve root that supplies skin and muscle further down.

Pain, tingling, or numbness is thus experienced at a place distant from the source of the problem. Biomechanical relationships in the arm are also altered which can add further irritation to any joint or muscle in the area.

Again, understanding the anatomy is crucial. Just like in the lower back, in between each vertebrae in the neck are discs with a fibrous outer ring and gel-like material in the center. Nerves come out of the spinal cord between the vertebrae, right where the discs are. This means anything that might cause the disc to bulge or herniate has the potential to affect the nerve root.

The nerves in the neck supply the muscles of the arms and provide the skin’s sensations in predictable patterns called dermatomes.

Doctors can use this knowledge to help determine what nerve root might be affected with someone experiencing, say, hand pain in their thumb and index finger.

Take another look at the dermatome photo. Pain in this area, in addition to simply being a problem local to the thumb, could also originate around the 6th cervical vertebra. Your doctor should be able to distinguish between the two.

Aside from the more obvious causes of shoulder or arm pain — falls, sprains, etc. — the most common cause of upper extremity pain I see in the office is habitual. That is, something we do every day as part of our normal routine or posture can bring about aches, pains, tingling, or numbness that seems to have no particular cause. This is prime fodder for the “I’m just getting old” or “I must be out of shape” explanations that float around the water cooler.

In particular, poor neck posture seems to be a major culprit. Anything that routinely brings the chin closer to the chest seems to lead to the type of pain described. Bringing the chin closer to the chest flexes the vertebrae in the neck forward. This position creates wedging of the vertebrae, with the front edges closer together and back edges farther apart.

Remember the discs between each of the vertebrae? When this wedging happens, the discs have to go somewhere. Being more fluid in nature, with the vertebrae wedged together in the front, the discs tend to push out toward the back. If this happens over a long period of time, eventually the discs can bulge or even herniate.

When any of this disc material — or any other anatomical tissue, for that matter — starts to abnormally push on a nerve, it’s a problem. The nerves at this level supply everything you can think of in the upper extremity. Shoulder pain, elbow pain, tingling down the arm, or pain in the wrist and hand are all fair game, to name a few.

So what qualifies as a bad habit? Reading in bed or watching TV with your head propped up. Routinely using a laptop or even a desktop computer with the monitor too low. Long periods of studying or writing with the material on the desk under your chin. Handwork, such as knitting, done with your hands close to your chest. Sleeping on your back with your head on a pillow that is too high, or on your side, curled up tightly in the fetal position.

There are many others. The bottom line is: if you keep your chin down close to your chest for long periods of time doing anything, you have the potential for this sort of problem.

The good news is that fixing this problem is generally not complicated as long as you find someone who can properly diagnose what’s happening. Once you’ve done that, treatment is relatively straightforward.

Chiropractic adjustments help tremendously. The adjustment has to be done in a position and direction where the nerve root is not impinged in any way. When done properly, this seems to clear the nerve root of any impingement and minimize any radiating symptoms experienced.

But the adjustment isn’t the whole fix. Lifestyle habits must be changed. In other words, keep your chin up!

This is crucial to keep the vertebrae aligned and free of any wedging so that things have time to heal. This is analogous to having your skin cut with a knife. The wound will heal cleanly with minimal scarring if it is dressed properly and the edges are held closely together with stitches.

On the other hand, if every day you go in and spread the wound apart with your fingers, you’ll be left with a nasty scar or, worse, the wound won’t heal at all.

Once the adjustment is made and lifestyle habits are addressed, residual issues can be tackled. Long periods of time with poor or diminished function and improper biomechanical support to tissue in the shoulder or arm can leave joints inflamed and muscles gnarly. Get in with a good Applied Kinesiologist, Rolfer, or massage therapist to work out the kinks.

Don’t let anyone tell you that the types of pains I’ve described here are a “normal” part of life. Keep your detective cap on and take an inventory of your usual activities that could be contributing to your condition. With a little persistence you can pass up that “normal” life for an optimal one!

With Texas temperatures regularly reaching triple digits, there’s no shortage of articles written about exercising in the heat. There are some highly respected exercise physiologists and coaches who have researched and given excellent explanations about what happens to the exercising body when mercury rises.

The bottom line is simple: you cannot exercise as vigorously in hot temperatures as you can in cooler temperatures. Conversely, if a rider performs at a given power output (i.e. workload) on a bike, and intensity measurements are taken, such as a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) or heart rate, both would be higher in hotter climes compared to cold.

For day-to-day training, conventional wisdom says that since heart rate increases as the temperature rises for the same power output, heart rate is a less valuable indicator of exercise intensity, since the muscles aren’t undergoing the same workload as they were in colder weather.

This is absolutely great exercise physiology, but doesn’t take into account the full spectrum of just plain old physiology. Our bodies are complete systems. Just because our muscles aren’t working very hard doesn’t mean that the rest of the body is on vacation.

One reason heart rate increases in the heat is because more blood is shunted from exercising muscle to the skin for cooling. Doing so requires a higher heart rate to maintain the same level of circulation to the tissues.

In addition, we tend to get dehydrated faster in hotter weather, which actually reduces our blood volume. This reduced volume also instigates a higher heart rate to circulate nutrients and remove waste. These factors alone place more stress on your kidneys, liver, brain, adrenal glands, and the heart itself.

This stress on your entire body is the reason you can do a moderate workout in 70 degree weather and feel great, yet do the same workout at 95 degrees and feel like you got up close and personal with the underside of an 18-wheeled vehicle. In other words, the workout in hotter weather feels harder because it IS harder.

Bodies like to burn an increasing percentage of sugars (compared to fat) in the heat, and this happens because different metabolic pathways are set in motion. This should tell us that we actually train our energy systems to varying degrees — and the metabolic pathways that go along with them, when we turn up the thermostat.

Basically, for a given workload, we don’t train the same muscles in the heat that we do in the cold. If you’re at all diligent about planning your training and being mindful of what kind of intensity you apply, and when–this should concern you.

The vast majority of endurance sports’ world records are set in cooler temperatures. Somewhere in the mid 50s Fahrenheit seems to be the magic temperature. We can’t subscribe to the idea that cooler temperatures make it easier to perform better without also agreeing that hotter weather will make it harder.

There are many who believe that given what we know about how heart rate increases in the heat, it should be less relevant or even ignored under those conditions. It should actually become more important given its usefulness as an indicator of systemic stress on the body. Unfortunately for our egos, this means that as the mercury rises we’ll have to slow down in order to train effectively.

A power meter is a great measurement of exercise intensity and a fantastic training tool, especially at levels of exertion above the anaerobic threshold, where heart rate data is truly less reliable. Used together, simultaneous heart rate and power measurements can show true gains or losses of fitness by pegging a relatively concrete indicator of workload (i.e. power) to a much more reliable indicator of intensity than perceived exertion (i.e. heart rate).

We shouldn’t ignore basic warning signs just because we have data that shows one particular area of our bodies isn’t working to the same extent in the heat. Your perceived exertion and your heart rate go up in hotter temperatures for a reason. Your body is trying to send you a message. Listen to it.

Stress comes in many forms. Most of us understand this intuitively. For example, we know that we feel “stressed” when we have a hard day at work or when we’re carrying a heavy load.

We use the word to describe an intense emotional event, and to convey what is happening to a wooden board bent to the point of breaking.

While the concept seems natural, the actual term “stress” hasn’t been around very long. It wasn’t coined until a researcher by the name of Hans Selye came along in the 1950s.

On the other hand, the idea that people and things could be subjected to environmental irritants has been around for a long time. D.D. Palmer, the founder of chiropractic, made this observation back in the late 1800s.

Palmer divided these irritants, or forms of stress, into three categories: mechanical, chemical, and psychological–or what he called “traumatism, poison, and auto-suggestion.”

An example of mechanical stress might be wearing an uncomfortable pair of shoes all day.

Chemical stress might arise from a food allergy or a toxin from unfriendly bacteria.

Psychological stress is perhaps the most well known, and can surface from any conflict such as a fight with your spouse or a bout with an unreasonable boss.

An important thing to understand about all forms of stress is that they’re cumulative. That is, you can’t separate the different varieties of stress and somehow recover from them independently.

If you spend the weekend playing touch football (mechanical stress) and have a looming work deadline early in the week (psychological stress), and as a result of your time crunch, scarf down fast food filled with sugar and hydrogenated fats (chemical stress), then it shouldn’t be a surprise when you’re worn down and sick by Friday!

Selye actually determined this half a century ago when he would stress lab rats in various ways and then observe how their bodies responded. No matter what form of stress, the eventual breakdown always followed the same pattern.

Humans also follow this pattern, and if we don’t make an effort to relieve the various forms of stress placed upon us, we end up sick, injured, or both.

So if various forms of stress can make us sick, then what exactly is health? It’s easy to understand that we feel good until mechanical, chemical, and psychological stressors (MCP) add up and we break down.

But what about that point in between when we have a fair amount of MCP, but we’re not yet sick or injured in any noticeable way (i.e. we don’t have any symptoms)?

That space in between the level of stress we’re currently under, and the level we have where we start experiencing symptoms is called “resistance”.

These ideas are best demonstrated with the stress chart at the top of the page, devised by Dr. John Bandy of Austin, Texas.

The chart reads like a thermometer, with our total exposure to environmental stress (or MCP), reflected by the “Now” point on the chart. Again, various types of stress can contribute to our total stress. Anything from marital strife, to fatty foods, to exercise can add to our overall stress level.

The point “D” on the chart is the Disease point. This is the point at which we begin to exhibit symptoms. “R” then, is a graphical representation of resistance. If the next big stress we are subjected to exceeds our current supply of resistance (“R”), then we experience symptoms of illness or disease.

At any given point in time we have varying amounts of resistance. It varies within and between individuals based on how healthful our diet is, what our job is like, how much exercise we get, whether a loved one recently passed away, and whether we’ve just been exposed to a “bug,” just to name a few factors.

That is, it varies based on how much MCP we’re experiencing.

So health, then, is that state in which we still have some resistance, keeping the level of environmental irritants that we are experiencing from producing symptoms. We are “unhealthy” (or experiencing “disease”), when MCP exceeds our resistance.

Any stress reduces the amount of resistance you have, bringing you closer to a state of disease. These concepts are well described in Dr. W.D. Harper’s book, “Anything Can Cause Anything.” The title gets to the crux of the matter: just like any expense — be it business or pleasure — will deplete your bank account, so too will any stressor deplete your overall reserve of health.

We’ll explore these ideas more next time to understand how we survive and adapt to all the stress that is around us!